The Khmer Rouge misdirect

Who were the Khmer Rouge and Why They Didn’t Kill Haing Ngor

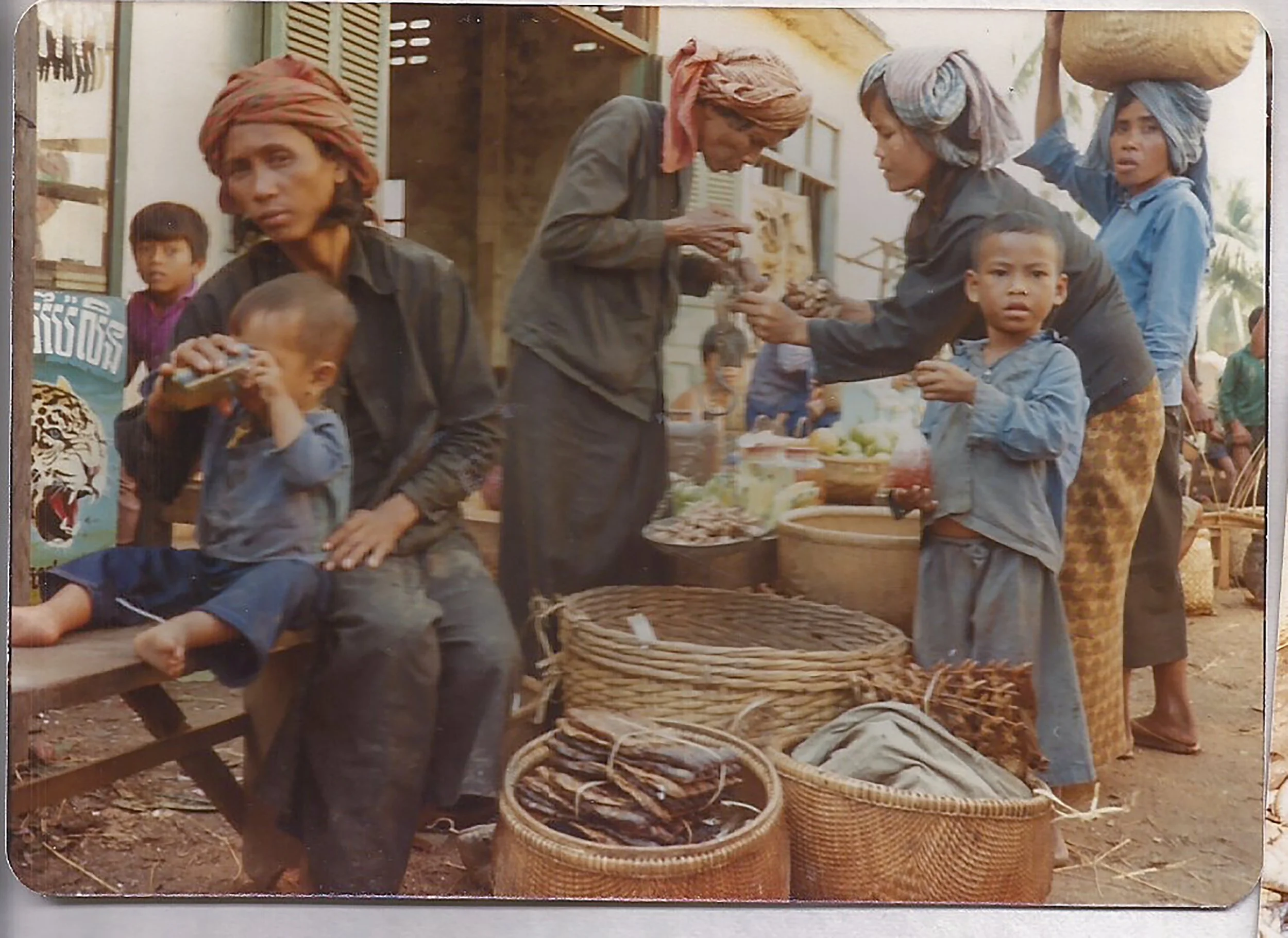

Cambodian civilians near the Thai-Cambodian border in the 1980s. Photo by RW

Below is the transcript to The Khmer Rouge Misdirect.

It’s the second episode of After the Killing Fields - Uncovering Haing Ngor

By Mary Patricia Nunan

INTRO: There’s a conspiracy theory that follows Haing Ngor around – even now, nearly 30 years after his death. It’s the notion that in 1996, Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot sent agents to Los Angeles to assassinate him.

It’s a tempting theory. Afer all, Ngor starred in the movie, “The Killing Fields,” which exposed the Khmer Rouge leaders for the genocidal maniacs they were, as well as the sheer scale of the destruction they wrought on Cambodia.

Ngor then used his fame to push for a human rights tribunal to hold Khmer Rouge leaders accountable for crimes against humanity – the millions of deaths they caused during their disastrous time in power.

To me, the idea that the Khmer Rouge killed Haing Ngor – is exactly that: just a conspiracy theory. Urban legend. But the glue that holds it together is all too real. It’s the unprocessed trauma that many survivors of the Khmer Rouge still carry – even decades after and continents away from 1970’s Cambodia.

My name is Mary Patricia Nunan, and this is After the Killing Fields – Uncovering Haing Ngor.

Investigating Ngor’s murder means eliminating motives and suspects – and I’m about to eliminate a big one. So who were the Khmer Rouge, and why does this theory still linger?

First - a warning – this episode will include scenes of Khmer Rouge brutality and torture.

TEXT: The simplest definition of the Khmer Rouge is that they were Cambodia’s homegrown communist insurgency. Their name just means “red Khmers,” a reference to Cambodia’s predominant ethnicity.

It was the late 1960’s and early 1970’s and communist movements were sweeping the world – Vietnam, Laos, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Colombia, Mozambique, Angola – the list goes on.

But the Khmer Rouge were different: after taking power, in April 1975, they enacted policies of staggering, fanatical violence.

SUSAN WALKER: When people say to me, it couldn't have been that bad, I said, the reality was much worse.

Susan Walker is a veteran humanitarian affairs advisor. She began her career as an aid-worker, with the American Refugee Committee, at the height of Cambodia’s refugee crisis.

That means she heard the stories of Khmer Rouge cruelty directly from survivors. Here’s what happened once when two young people fell in love.

SUSAN WALKER: The couple was put in the middle of this youth camp that the Khmer Rouge had taken people. They would put ropes around their neck and all the other kids had to walk around and kill - until the boy and the girl were killed. How do you survive from that? They banged babies against trees until they die. How do you survive that? Gutting pregnant women and then banging the fetus against the tree.

Khmer Rouge goals were delusional from the start: they wanted to create a utopian communist society. Wholesale slaughter of their own countrymen and women was their method for getting there.

Once they seized control of the country, they marched everyone out of the cities at gunpoint, and into forced labor camps – the entire population of between 7-8 million people, suddenly imprisoned.

Then they “filtered” people. Peasant rice farmers, the “proletariat,” were considered the purest type of Khmer. So the Khmer Rouge executed anyone from the professional class for the crime of being “bourgeois.”

That’s why a doctor like Ngor, or Dith Pran, the New York Times reporter that he played - had to pretend they were uneducated and working class.

Torture was the penalty for any perceived infraction of the rules, or the mere suggestion one wasn’t loyal to the revolution or its leaders. Pol Pot, the leader, was revered, but rarely seen.

This is Ngor in 1985. That’s the year after “The Killing Fields"” came out. This is what he said to high school students, believe it or not, at Punahou School, in Honolulu, Hawaii.

NGOR: He tied me up over here – both sides of hands, tied up. And both legs – hanged up, crucifixion style, like Jesus Christ. And start fire at the bottom for three nights and four days.”

Ngor’s accent can be tough to follow, so if you didn’t get that: the Khmer Rouge strung him up on a cross - crucifixion style, and lit a fire beneath him for three nights and four days.

That wasn’t the only time Ngor was tortured. We’ll hear more about his experiences in an upcoming episode.

The Khmer Rouge thought their revolution was so pure, that they had re-set the calendar, to “Year Zero.” They banned money, private property, books, film, music, religion – all signs of a corrupt, capitalist society. They took a reasonably modern country and tried to brutalize it into a pre-industrial Eden. It was spectacular failure.

You know how Americans can tell you where they were on September 11th, 2001?

AUDIO – MONTAGE – voices discussing the people they lost

In Cambodia, anyone alive between 1975 and 1979 can run through the number of family members they lost to the Khmer Rouge – sometimes reaching into the dozens.

Hundreds of thousands of people escaped to refugee camps dotting the border between Cambodia and Thailand. At least 2 million died during the Khmer Rouge reign, according to DC Cam, a Cambodian non-governmental organization which documented the atrocities. That’s at least one quarter of the population.

He may not get as much attention in American classrooms. But Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot ranks alongside Hitler, Stalin and Mao as one of the worst war-criminals of the 20th century.

[AUDIO / NEWS SERVICE]

That gives you an idea of the sheer scale and brutality of the Khmer Rouge period. But no conversation about them is complete without a little more history.

Cambodia shares a border with Vietnam – where in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, the US was busy losing a war.

The North Vietnamese routinely criss-crossed that border, to run supplies to their fighters further south. In response, the US carpet-bombed the Cambodian countryside, in an attempt to wipe those supply lines out. That was President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, to be precise.

Cambodia’s monarch, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, had declared the nation’s neutrality in the Cold War conflict. But in 1970, he was ousted in a coup – which many say was orchestrated by the CIA, although there’s still debate around that. Still - that same year, the US military illegally invaded Cambodia. Once again, it was about trying to win in Vietnam.

The Khmer Rouge had been a small, homegrown communist insurgency. Prince Sihanouk was so angry about the coup that he urged Cambodians to join them. Hundreds of thousands - many, sharing his anger at the US – did exactly that.

[BREAK]

Now, let’s circle back towards Haing Ngor.

The Khmer Rouge were obsessed with purity – any traitors to the revolution had to be purged.

In charge of much of that purging was a Khmer Rouge official named Comrade Duch. His real name was Kaing Guek Euv. He ran a prison, called Tuol Sleng, or S21. That’s where disloyal Khmer Rouge, and other unfortunate souls, were tortured and most – later executed.

This audio is from 2009. Haing Ngor has been dead for 13 at this point. But one of his wishes came true. The remaining Khmer Rouge leaders were being put on trial for war-crimes. The first to testify was Comrade Duch.

TRANSLATOR / DUCH’S TESTIMONY: “If we talk about Pol Pot, he was the highest person. He really designed the theory and the line to destroy - to kill people heinously.

Comrade Duch’s testimony is being translated by the tribunal’s official interpreter.

TRANSLATOR / DUCH’S TESTIMONY: I believe that Pol Pot used a kind of trick used by Stalin when he killed Trotsky in order to kill Haing Ngor and me and my wife. Luckily, I survived. Unfortunately, my wife died. Haing Ngor was killed because he appeared in the film, “The Killing Fields.”

Duch testified in 2009, with zero evidence, that Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot ordered the assassination of Haing Ngor, in Los Angeles.

That one line of testimony made headlines. It reignited the conspiracy theory that first emerged with Ngor’s death in 1996.

DUNLOP: There is a great, incredible chauvinism amongst a lot of Cambodians. And I think that the whole purpose of these purges was to a constant process of revolution of purging of cleansing of ridding the ranks of enemies, and they were deeply secretive and very, very paranoid.

This is Nic Dunlop. He’s an Irish photo-journalist who, in 1999, found Comrade Duch living in a remote part of Cambodia, under an assumed name. It was a discovery that eventually led to Duch’s arrest, and this 2009 testimony.

DUNLOP: And they were convinced that their revolution was unique, that it was the most far reaching and radical revolution the world had ever seen. And they believed that it was the envy of suddenly the communist world and they were paranoid about the Vietnamese for instance, undermining that revolution. So, you know, I think the whole idea the whole concept of being Cambodian or being Khmer and being pure of pure blood was central to the Khmer Rouge thinking.

By 1977, after two years in power, the “revolution” began to eat itself.

Purges became so common that key, mid-level Khmer Rouge officers fled to Vietnam. There, they got organized. And on January 7, 1979, Vietnam invaded Cambodia – overthrowing the Khmer Rouge.

Cambodians call it “Liberation Day.” But the invasion also ignited the four-way civil war that would grip Cambodia until the 1990’s.

Pol Pot and other senior leaders disappeared into hiding – still commanding their forces from deep within the territory they controlled. Duch disappeared too.

Dunlop wrote a book about Comrade Duch called “The Lost Executioner.” He’s with me on the conspiracy theory about Haing Ngor’s murder.

DUNLOP: If that was under the orders of Pol Pot, you'd wonder: Well, why? I mean, of all the Cambodians, why would you go to great lengths to have somebody assassinated in the United States? To what end? To what purpose?

Ten years passed between Comrade Duch’s arrest and his testimony at the Khmer Rouge tribunal – officially called Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. To Dunlop, Duch was playing for sympathy.

DUNLOP: I think the Khmer Rouge were too inward-looking to be that organized to organize an assassination on the other side of the planet. I just don't think that's possible. At least I think it's highly unlikely. Possibly it's about him. Duch positioning himself, closer to the likes of Haing Ngor, who was clearly probably one of the most famous Cambodians after Sihanouk certainly in the in the western, so it was pretty much for a western audience and remember, he was very aware of his audience in court,

One simple reason it’s so implausible the Khmer Rouge killed him is simply… time. “The Killing Fields” came out in 1984 – so why not kill him then, or sometime during Ngor’s years of campaigning against the Khmer Rouge in the 1980’s? Why not kill him in Cambodia? It would be much easier than sending agents to Los Angeles, or even calling on a sympathizer there to do the deed.

One thing that makes "The Killing Fields" so extraordinary is that it’s credited with helping inspire Cambodia’s peace deal. Those negotiations - largely - brought an end to Cambodia’s four-way civil war.

That deal was signed in 1991. A massive United Nations peacekeeping mission was deployed to Cambodia. The UN’s goal was to supervise democratic elections in 1993.

[AUDIO – UN archive]

The people who think the Khmer Rouge killed Haing Ngor are quite simply overlooking a huge amount of history – tied in with the peace process.

You see, in 1993, the Khmer Rouge made a massive strategic mistake: they pulled out of that peace deal. They refused to participate in the elections. That was their decision.

The Khmer Rouge thought their absence would undermine the entire UN mission. They were wrong. The 1993 elections were a fabulous success; and the Khmer Rouge had sidelined themselves.

Now technically, the Khmer Rouge held dwindling pockets of territory and you still wouldn’t want to run into them. That would probably be fatal.

By the end of 1993, when the UN left, the Khmer Rouge were left sitting in the jungle. The rest of Cambodia blossomed into the future.

If you think about it, when I was there, in the 1990’s, virtually the only images we ever saw of Pol Pot were in black-and-white. The Khmer Rouge were an increasingly a bizarre relic of the 1970’s. That was part of the allure.

The same year Ngor died, 1996, a senior Khmer Rouge leader named Ieng Sary defected to the government. He brought with him thousands of fighters. The Khmer Rouge were in their death throes.

[BREAK]

I’m going to throw two more experts at you – who also debunk the conspiracy theory.

Nate Thayer was one of the world’s foremost experts on the Khmer Rouge. In 1999, he accompanied Dunlop, in their historic confrontation with Duch - that eventually led to the war-crimes tribunal. Two years earlier, Thayer had interviewed Pol Pot.

In the last episode I told you how I am collaborating with the Innocence Center for this investigation. They’re the legal non-profit that represents one of the wrongfully convicted in the Ngor killing. Most of the time, I’m collaborating with Frank – the Innocence Center’s research consultant.

“Frank” is not Frank’s real name – he prefers his privacy when it comes to podcasts. But he’s a retired police officer, with years of investigative experience in gang violence - including Asian gang violence - in southern California. He’ll come up more as this podcast goes along.

This audio is from an interview Frank did with Nate Thayer in 2018. Thayer has since passed away. Frank asked Thayer if the Khmer Rouge could have killed Ngor in LA.

THAYER: Operationally virtually impossible. They certainly would have no control over --... It's not like they control gangs or criminal gangs…. you'd have an operational control and there's, there's just no way - particularly the Khmer Rouge.

In Cambodia, Youk Chhang, is the Executive Director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia – better known as “DC Cam.” It’s the non-governmental organization that that investigates, collects and preserves evidence of Khmer Rouge atrocities.

CHHANG: For me it’s not a Khmer Rouge assassination. Not at all.

MPN: Yeah, that's a theory that comes around and Duch – he perpetuated that idea – that Pol Pot sent –

YOUK CHHANG: I think it's easy to blame Khmer Rouge for everything, but sometimes thing happen out of the Khmer Rouge context

[BREAK]

I want to linger here for a moment with Youk Chhang to underline the significance of "The Killing Fields" as a movie. After the Khmer Rouge were overthrown, the government showed “The Killing Fields" on state-run tv, multiple times a year.

CHHANG: I think they show this on May 20th, April 17, January the 7th, anything dealing with the Khmer Rouge, they show that film. It was the the only film.

For Vietnam, which had ousted the Khmer Rouge when they invaded -- the movie helped justify their occupation of Cambodia. To Chhang, it’s also almost as if the film served as an early human rights report.

MPN: And what was their point? Just to prove that the Khmer Rouge were horrible?

YOUK CHHANG: No, I think was that because the world don't seem to believe that genocide took place in Cambodia. It's about genocide. It was a genocide campaign from [the] beginning.

[BREAK]

Getting back to the conspiracy theory, I could go on, detailing the Khmer Rouge death throes. To summarize, after their disastrous decision to withdraw from the UN peace process, the Khmer Rouge spent the next five years trying to find a way back into Cambodia’s political mainstream. They were desperate to dissociate themselves from the 1970’s – and the war-crimes for which they were renowned.

Killing Haing Ngor in 1996, in some sort of belated revenge killing for a movie that came out 12 years earlier? It simply makes no sense – the Khmer Rouge would have been undermining their own goals.

On top of that, Comrade Duch hadn’t been arrested yet in 1996 - that didn’t happen until 1999. So there was no genuine momentum toward an actual human rights tribunal taking place. The Khmer Rouge leadership had neither the motive nor the means to kill Haing Ngor.

[BREAK]

So what makes this conspiracy theory so sticky? It’s nearly 30 years later, and the idea that the Khmer Rouge killed Haing Ngor lives on in certain circles.

I believe the answer is trauma – the overwhelming amount of unprocessed trauma suffered by far too many people in Cambodia’s resettled refugee community, in Los Angeles. Haing Ngor’s second home.

DEATH IN CAMBODIA - PODCAST

Dorothy Chow is a Khmer-American living in San Francisco. She was born in the US, but her parents are survivors of the Khmer Rouge.

When the pandemic set in, she launched the podcast, “Death in Cambodia,” to tell her father Robert Chau’s story of survival. Her mom would still rather not share hers. (For the transcript: father and daughter spell their names differently. It was an immigration glitch.)

Dorothy Chow’s too young to be in the loop on Haing Ngor. In fact, when I interviewed her, she hadn’t seen “The Killing Fields.” But she wasn’t surprised when I told her that former refugees – many of whom live in and around Long Beach, California – thought the Khmer Rouge assassinated him.

DOROTHY CHOW: During the Khmer Rouge people who were artists and educated people were the first to go. They were the ones that were being targeted during that time. Somebody like a successful artist would be, would be a target, you know, during the Khmer Rouge, so it doesn't really surprise me then that, you know, people within the Long Beach community went to that conclusion.

Her podcast began as a pandemic project, but it became much more. Chow launched “Khmer Courageous Conversations.” She works with a licensed clinical psychologist to host online support meetings for people like her: first-generation Americans, who are also second-generation survivors of the Khmer Rouge.

DOROTHY CHOW: All these refugees who came in here never had an opportunity to really process whatever happened. And even to this day, as I run the podcast, I get a lot of DMs and messages from other, you know, second generation Cambodians who say that their grandparents still have nightmares about the Khmer Rouge. I mean, there's very, very much deep trauma that is unprocessed within the community.

[BREAK]

I’ve come to think of this conspiracy theory as “the Khmer Rouge Misdirect.”

It makes perfect sense to me that survivors of the Khmer Rouge were triggered by the news of Ngor’s death. He was a hometown hero. I have no doubt that many, suffering from unprocessed trauma, became fearful that the Khmer Rouge could still reach them, even overseas.

Part of it was just the sheer scale of Khmer Rouge brutality. Sometimes I think of the Khmer Rouge like someone threw a rock into a pond. Historically, it wasn’t THAT long ago – and the ripples are still receding.

For the record, zero evidence has ever emerged to suggest the Khmer Rouge killed Haing Ngor – no matter what Comrade Duch might have said. American authorities appear to have quietly ruled out the possibility of a Khmer Rouge assassination on US soil.

But I also have to wonder if this conspiracy theory prevented larger questions from being asked.

There are news stories and true-crime shows that consider the Ngor case - and the arrest of the three gang members -- a triumph of police work. Others leave the discussion open-ended -- yet another intriguing mystery about the secretive Khmer Rouge. It’s an entirely valid question to ask.

But that means here has been virtually NO examination of the international dimensions of Ngor’s life. His business interests. His business partners. His family. His sex-life. His feuds. And the death threats he received.

Ngor was straddling two worlds. He stayed as active as he could in Hollywood, to make money from acting in films and tv. Then there were the humanitarian projects and businesses he was trying to get off the ground in Cambodia. He quickly hit some rough spots.

What’s more, unprocessed trauma will continue to play a part in Ngor’s story. I believe Ngor’s likely PTSD was a contributing factor to his death.

I mentioned in my opening episode, that there were multiple motives for killing Ngor. I don’t even count the Khmer Rouge conspiracy theory among those. There are others.

That is the point of this podcast – to look at Ngor’s life in Cambodia. That’s where he hit the turbulence that that led to his murder.

This episode has been super analytical – historical. We had to dive in here. Future episodes are going to be more about field work, and more about the journey, I promise.

The Khmer Rouge didn’t kill him. Of that, I am confident. I hope you’ll stick with me, as I collaborate with the Innocence Center and I try figure out who did.